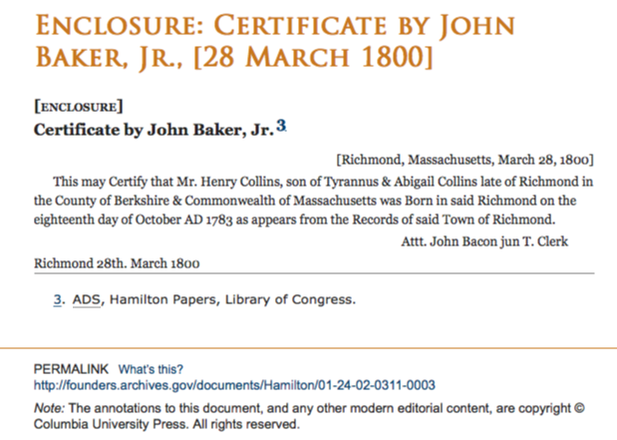

The RecordsThe National Archives has partnered with the University of Virginia to make historical documents of the Founders of the United States of America free and available online. On the website Founders Online, you can search through thousands of digitized records from George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. The site is continually being added to and will include over 178,000 documents relating to America's Founding Era when it is completed. To get started, there is a FAQ page "How to Use This Site" for tips on how to find, access, and research documents in the collection. Whether researching a person, time period, or a concept (e.g. Bill of Rights), you can find specific suggestions and helpful information there. The collection can be searched in several ways: by author, recipient, time period, or keyword. The documents are fully searchable and annotated. The Case StudyAs an example of how valuable this digital collection can be for genealogists, I will use a case where I was working on identifying the death date of a Revolutionary War patriot from New York. If you have ever worked with colonial era records, then you know it is often difficult (if not frustratingly impossible) to locate documents for an ancestor going back that far. Some states, and even towns within a state, were better than others at keeping track of vital records at that time. After exhausting town and church records search, the goal is to look next for other types of records that hold clues about that ancestor. In the case of my patriot, I needed to track his family's whereabouts after the Revolutionary War ended. What little I knew about him was that he was born and had married in Connecticut, and moved to the small frontier town of Ballston, New York when it was first settled. During the Revolution, he was taken prisoner by raiding Tory soldiers and held in Canada until the fall of 1782, when the last of the Patriot prisoners were released and sailed for home. Unfortunately for me, he did not go straight back to his farm in Ballston, NY. After the raid where he was taken prisoner, it was apparent that his wife and children had not remained in the town. They had probably fled to be near extended family or former neighbors in a safer place, but where?? At that early stage in my research, locating that unknown community was like finding a needle in a haystack. The ancestor's first name was unique ("Tyrannus") but also frequently misspelled in records, so using name variations and wildcard characters in searches could take a very long time. Last name was common ("Collins"), which would also return too many records during index searches to be productive either. When it comes to colonial research, as I have already mentioned, vital records can only be so helpful. Census records are the next go-to place, but the first U.S. census of householders are fraught with errors and omissions. Because the family didn't show up in the first 1790 U.S. federal census in either New York or Connecticut, I needed to strategize another way to get a handle on where they might have gone. The first stop was to look at early post-colonial era collections for general information that might pertain to the ancestor and his family. That is where the Founders Online collection came in. It truly was as simple as typing the ancestor's name "Tyrannus Collins" in the keyword search bar. Of course, we all know about serendipity, which isn't always on a researcher's side. But when it is..."Eureka!" moments like this are priceless: I not only found the town where the patriot had gone right after the war, I also confirmed that his youngest child was born there and that they had left town afterwards. I have since identified much more about the patriot's personal story up until his death and I owe it to this simple affidavit for helping knock down a brick wall that has made other researchers give up. Source: Founders Online. https://founders.archives.gov. 2017

1 Comment

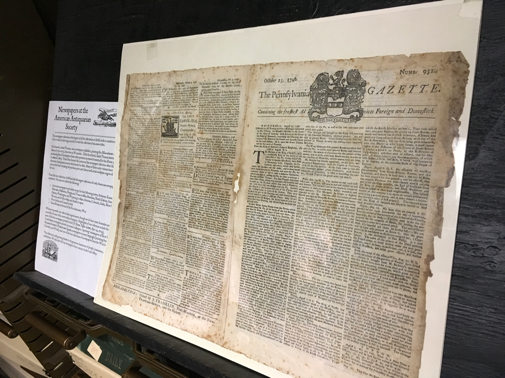

Today I visited the American Antiquarian Society (AAS) in Worcester, Massachusetts where Jim Moran, the AAS’s Director of Outreach, arranged with the local group History Camp-Boston for a special behind-the-scenes talk and tour. This incredible archive is the repository for all things printed in our country’s 50 states, ranging from 1640—1876. These dates directly correspond with the operation of the first printing press in Boston through the enactment of copyright laws by the Library of Congress. In 1876, 2 copies of any publication made in America were required to be sent to Washington; because the LOC had a stable and larger infrastructure for housing the materials, the AAS cut off the collection as of that year and turned its focus to acquisition. This strategy has made the AAS an archive of national scope that every researcher should include in his/her go-to repository list. About the AASThe AAS was founded in 1812 by Revolutionary War patriot and local printer Isaiah Thomas. During the colonial years, when he ran his own very successful business in Massachusetts, his passion was to collect samples of publications from printers throughout the colonies. He wanted to study and compare technology and materials, with the collateral result of amassing an important historical collection. This was the birth of the AAS as both a learned society and a major independent research library. The Collection The AAS library today houses the largest and most accessible collection of books, pamphlets, broadsides, newspapers, periodicals, music, and graphic arts material printed through 1876 in what is now the United States. Predating the New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS) and New York Genealogical and Biographical Society (NYG&BS), the AAS also holds manuscripts and a substantial collection of secondary texts, bibliographies, and digital resources and reference works related to all aspects of American history and culture before the twentieth century. Types of ephemera run the gamut from 1814 voter ballots from a single town to inserts that were tucked into boxes with new watches. Most impressive, however, is the scope and depth of the newspaper archive. Access the ManuscriptsThe collection has been fully digitized up through 1820, with finding aids for the subsequent years. The entire digital collection can be accessed on site at the AAS. Remote (at-home) access is available for a small portion of the collection. Where AAS has partnered with outside vendors, such as GenealogyBank.com and Ancestry.com, the vendors only have a portion of the full collection in their databases. If you are planning to research on site at the library, visit the AAS website for how to plan and what to expect. The library is closed-stack and non-circulating. Visitors fill out call slips for item retrieval and view the materials in the reading room. Non-flash photography is encouraged, with photocopying and digital imaging services also available. Typesetter Trivia!The metal letters used in hand setting a printing press were stored in a case of wooden drawers next to the printing press. This is Isaiah Thomas's actual LETTER CASE on display at the AAS, To be time efficient, and to be able to work quickly without looking, typesetters arranged the letter blocks in a specific order: the most frequently used letters were placed in the LETTER CASE where they could be reached easily. Specifically, the capital letters were stored in the UPPER CASE and the regular letters were stored in the LOWER CASE. (And now you know where those terms originated!) American Antiquarian Society

Address: 185 Salisbury Street, Worcester, Massachusetts 01609 Tel.: 508-755-5221 Email: [email protected] Website: www.americanantiquarian.org |

AuthorBeth Finch McCarthy

|