|

April 1, 2022 will be a huge day in genealogy-land! That is the date that images of the 1950 U.S. population census will be released to the public. (This follows the law that a census cannot be made publicly available until 72 years after the official census day.)

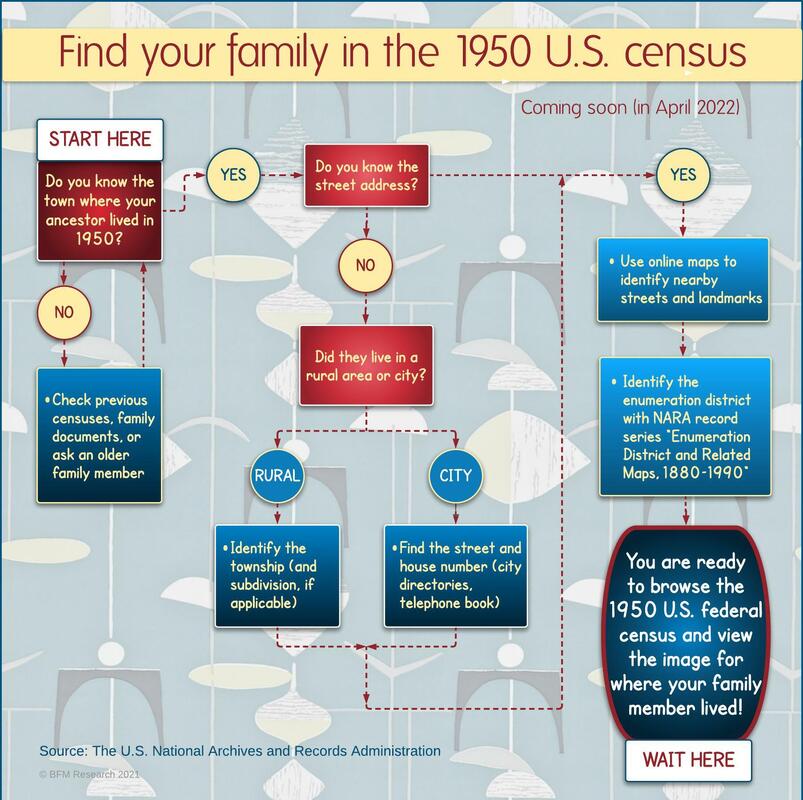

The good news is that you will see images of the actual census pages that the enumerators filled out. The not-as-good news is that they will not be searchable by an ancestor's name until sites like Ancestry.com, Fold3.com, or Family Search create indexes and databases for you. And that will take several months of many people working many hours to get that done. The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) may use handwriting recognition technology to provide a name index soon after. Still, you can imagine that it won't be particularly accurate. (I mean, I can't even read my OWN handwriting sometimes, so...) You can wait impatiently for months until a searchable database becomes available, or you can do some homework and get the job done much more quickly. The key is knowing the street address of where your ancestor lived that fateful day in 1950. Identify the correct enumeration district (ED), and you will be ready to browse the images and track him down in no time (sort of). My infographic above follows the research process by asking you a few questions and setting you up for success when the clock strikes midnight on March 31! PINPOINT WHERE YOUR ANCESTOR LIVED IN 1950 A street address for a city-dwelling ancestor is like gold here. If he/she lived in the country, then a township or subdivision of a rural area will work. But if you don't know where their residence was, there are ways to figure it out. If you are super lucky, someone in your family might know. Or poke around in the family records you already have for some clues. Hint: if you know where they were on the 1940 census, try following their path with city and phone directories. If the street still exists, you can find it with online mapping tools like Google Maps. If the street is gone or was renamed, seek out historical maps from earlier in the 20th century. Either way, familiarize yourself with main streets and landmarks in the neighborhood because one of those will likely be a boundary line of an ED. IDENTIFY THE CENSUS ENUMERATION DISTRICT (ED) FOR YOUR ANCESTOR'S RESIDENCE The purist's way of determining the ED for your ancestor is to find his location on the original Census Bureau's maps. The National Archives Catalog has digital images of the 1950 census ED maps in the record series, "Enumeration District and Related Maps, 1880–1990." In addition to the political jurisdictions (county, city, township), the maps show roads, waterways, and large properties like cemeteries and parks. City maps often label ward boundaries and other types of subdivisions. The ED numbers are written in orange and have two parts: 2-digit prefix for county and 2-digit suffix for a specific area in that county. Do you prefer the click-and-go method? I can still hear my math teacher lecturing me, "You need to know how to calculate the answer yourself before I let you use a calculator!" The value of that wasn't lost on me, particularly when my solar calculator ran out of power during a test. And I did just give you the tools to determine your ancestor's ED by hand. But lucky for you, tech wizard Steve Morse created the One-Step-Webpages site where the magic can happen much more quickly. On his Unified Census ED Finder page, you can type in as much information you know about your ancestor's location, and the ED will be spit out for you. So, get all your ancestors' 1950 data pulled together now, and you will be ready to roll when the 1950 census is made available to the public. Happy hunting! Additional sources: 1950 US census research guide on FamilySearch How to research census records with the NARA website NARA's 1950 census blog 1950 US Census Bureau History NARA blog about online public access to its records

9 Comments

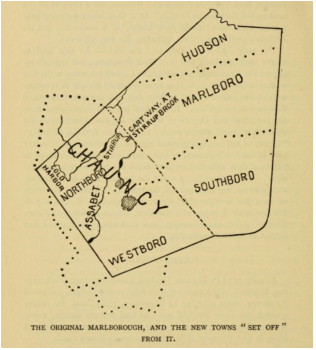

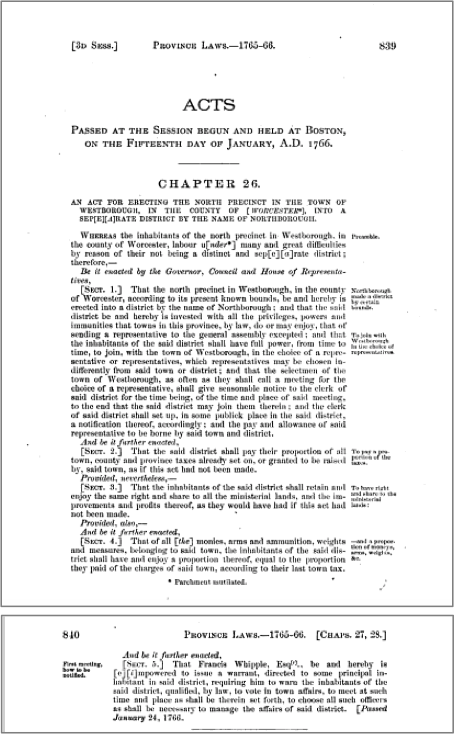

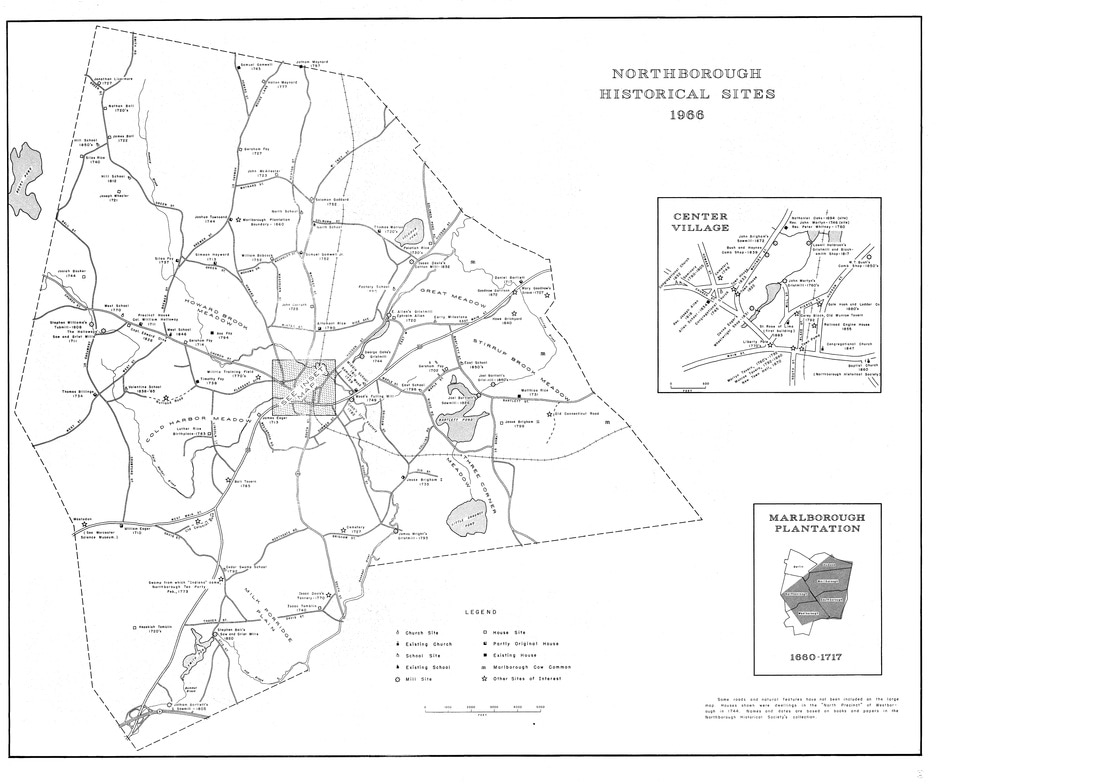

In 1966, the town of Northborough, Mass. celebrated its 200th anniversary of becoming a town. The first inhabitants on the physical land were there decades before the 1766 separation from the parent town of Westborough. This map, created by the Anniversary Committee in 1966, identifies many of the historical homesites going back to 1660. While the general layout of the town hasn't changed much over the last 50 years, one major event changed the character: the building of Rt. 290. In the sections where the highway overpasses could not be built, roads were either rerouted or cut in 1/2 and turned into cul-de-sacs. So if you are headed for an address on Howard Street, you'd best check a map first to see which end you have to get to first! A full size version of the map is here.  1966 Map of Northborough (Worcester Co.), MA with Historical Sites Overlay. Front view. (courtesy Northborough Historical Society) 1966 Map of Northborough (Worcester Co.), MA with Historical Sites Overlay. Front view. (courtesy Northborough Historical Society) Map of original Marlborough Plantation with modern town overlay (from The History of Westborough) The way New England towns were settled by the English was actually very common across Massachusetts. Religious dissenters (primarily Puritan) established communities where there was plenty of land and other natural resources and followed traditional English laws. Towns were built around the Meeting House, the central location of all things religious and political. Residents were primarily farming families. Couples bore many children to work the family farms and faced the odds of losing some to diseases like smallpox or the flu. After a few generations in those early communities, there was not enough open land for the increasing number of growing families. Surveyors headed westward to find new areas for establishing new towns. For example, the early colonial town (or “Plantation”) of Sudbury, Massachusetts became crowded and a handful of young men set off to find a new home in the adjacent combined lands of what is now Marlborough, Hudson, Northborough, Westborough, and Southborough. In that manner, "Marlborough Plantation” was settled in 1656 and the first settlers lived near the center of modern Marlborough, farming land in the outer areas of the town. Over subsequent generations, families continued to grow in number and needed to find more living space outside of the center of Marlborough Plantation. A village a few miles west at Lake Chauncy sprung up (the "west borough"), where farmers of the western stretch of the Plantation (Northborough and Westborough combined) could live closer to where they worked during the day. However, the new village was inconveniently far from the Plantation Meeting House; it was a slow and hilly trip back to the meeting house every Sunday. It followed that once there was enough people living in Chauncy to warrant building their own meeting house, hiring their own minister, and “managing their own affairs,” the villagers petitioned for separation from Marlborough. In 1717, the new independent town of Westborough was officially established and comprised the lands of modern Northborough and Westborough. When the Westborough meeting house moved from Lake Chauncy to three miles south to the center of modern day Westborough, there were well over 30 families living in the “north part” of the town who again found themselves facing a very long and difficult trip back and forth on required meeting days. Can you just imagine the families, on an early wintery Sunday morning, trying to be up, dressed, and ready to march down the hazardous road [what is now Rt. 135] to church in Westborough Center? The devoted northern Puritan families were outraged even more by the inequity of their situation when finding themselves at funerals without a minister; he himself did not like to make the long trek up north to Brigham Street Old Burial Ground. To address these religious concerns, the northern family heads met and petitioned in 1744 to become a precinct of Westborough. Note that a “precinct” was distinctly different from a “town”: the newly formed Northern Precinct would have its own meeting house and preacher but would remain politically and fiscally a part of the town of Westborough. Over the two decades following the 1744 petition, there were lingering serious challenges because the Northern Precinct was not fully independent from Westborough. For example, elected northern officials found it difficult to travel south to important town meetings and represent the interests of the northern families. Another problem was that the Northern Precinct was viewed as only one of the town's three school districts and the teacher was not available full-time in any single district. Adding fuel to the flame, no funding was made for Northern Precinct schools, highways, or other types of community improvements. To finally achieve the independence they had sought and desired for so long, town founders successfully presented a petition to the General Court in Boston. The District of Northborough was officially formed on the 15 January 1766 and the district became a fully-fledged town on 23 August 1775. SOURCES: Clifford, John Henry et al. The Acts and Resolves, Public and Private, of the Province of the Massachusetts Bay: to Which are Prefixed the Charters of the Province with Historical and Explanatory Notes, and an Appendix, Volume IV. Boston, Massachusetts: Wright & Potter, 1890. DeForest, Heman Packard and Edward Craig Bates. The History of Westborough, Massachusetts. Westborough Massachusetts: Town of Westborough, 1891. Kent, Josiah Coleman. Northborough History. Newton, Massachusetts: Garden City Press, 1921. Parkman, Ebenezer. The Diary of Ebenezer Parkman (1703-1782): First Part, Three Volumes in One (1719-1755). Francis G. Walett, editor. Worcester: American Antiquarian Society, 1974. Happy 250th Birthday, Northborough! In 2008-9, the Town of Northborough contracted to have historically significant properties identified. Prefacing the final report of the several hundred homes and landmarks is a concise yet comprehensive summary of 300 years of local history and one of the best go-to finding ads for understanding the "big picture." Individual properties included in this report were evaluated for historical significance. The property summaries include the identities of previous owners as well as associated historical events and socioeconomic developments. Original source materials were used for the survey and it serves as an excellent encyclopedia for kicking off research at a local level. The following narrative is Part III the complete document, the remainder of which can be found on the Northborough Historical Commission's website. NARRATIVE HISTORY OF NORTHBOROUGH, MASS. Northborough is a town of 18.8 square miles in Worcester County, Massachusetts, situated about 8 miles east of Worcester and 35 miles west of Boston; the population at the last census (2000) was 14,013. Although some settlement occurred in the late 17th century, English occupation of what would become the town of Northborough principally occurred in the early 18th century, after hostilities with Native Americans had ended. A Congregational society was established in 1744, giving it a separate identity, but until 1766 Northborough remained a part of the adjacent town of Westborough. Throughout much of its history, the economic base of Northborough has been agriculture. After 1800, some “cottage industries” developed into factory-based production, most notably the making of shoes and combs, and along the Assabet River there were a few small-scale woolen mills. The center of Northborough developed as an institutional focus for the town, along with a small commercial district, a settlement pattern further encouraged by the completion of a railroad to Northborough in 1856. During the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century, Northborough experienced both a population increase and an increase in ethnic and religious diversity, and relatively densely built residential neighborhoods, some with concentrations of particular ethnic groups, clustered around the town center. As the woolen mills prospered, the stock of company-built housing increased, creating small mill villages at Woodside and Chapinville. In this period, Northborough developed some of the institutions characteristic of larger towns and small cities: consolidated schools, a high school, a public library, and fire and police services. After World War II, suburban-type residential development began to alter Northborough’s predominantly rural character, but even today Northborough retains much of its small-town feel. Reading in general works on Northborough history, as well as the site-specific research undertaken to complete the forms, identified a number of historic themes or contexts: Agriculture Agriculture formed the basis of Northborough’s economy and social structure from the inception of English settlement until the second half of the last century. A settlement pattern of widely dispersed family farms characterized the 18th and early 19th centuries and is still evident today in the old houses and barns that appear scattered among modern residential development. The agricultural economy also gave rise to the institution of the one-room district schoolhouse: a centralized system of education was not appropriate for a community in which people lived long distances from the town center. Agriculture in Northborough evolved over time, particularly in the period (ca. 1860 – 1906) covered by Phase II of the survey. The generalized, near-subsistence agriculture practiced in the colonial and early national eras was supplemented in the second half of the 19th century by market-oriented production. With railroad connections to Boston and beyond, Northborough farmers were able to produce dairy and orchard products for sale, as well as eggs and tomatoes, asparagus, celery, and other vegetables. Some Northborough farmers supplemented their income by renting out teams of horses and equipment for reservoir construction, and others benefited from selling their timber for use as ties by the railroad and trolley line. The survey identified scores of houses associated with farming families, as well as a number of properties that retain sizeable barns: 363 Crawford Street (NBO.242), 110 Howard Street (NBO.250), 87 Pleasant Street (NBO.289), and 536 West Main Street (NBO.326). The building at 10 Blake Street (NBO.235) recalls the increasingly market-oriented activities of Northborough’s farmers: it appears to be a substantially modernized incarnation of the Northborough facility of Deerfoot Creamery, a major supplier of milk and other dairy products to the greater Boston region. Industry Like most Massachusetts towns, Northborough developed an industrial sector in the 19th century. However, the waterpower available from the Assabet River and other Northborough streams, while useful for the gristmills, sawmills, and fulling works that were part of the agrarian economy, was inadequate for large-scale manufacturing, and so most industries remained small, with relatively few employees and modest production. Valentine’s 1830 map of Northborough identified 14 buildings as shops or factories, besides textile mills. The production of textiles in Northborough was centered at two locations that eventually became known as Woodside and Chapinville. The Northborough Cotton Manufacturing Company, chartered in 1814, began both cotton and woolen manufacturing at a site on the Assabet River that had earlier been exploited for a gristmill. The company remained in operation for 20 years and then went through repeated changes in ownership; the mill itself burned in 1860. In 1866, David F. Wood bought the property and erected a woolen mill on the site of the old cotton mill. He successfully manufactured woolens until his death in 1900, and his company gave the name “Woodside” to the vicinity. Later textile manufacturers at the site include the Woodside Woolen Company, the Taylor Manufacturing Company, the Chilton Company, and the Northborough Textile Fibre Company. The mill complex, dating from 1888, survives (200 Hudson Street, NBO.266), as do a number of associated areas of mill-owned houses (NBO.N, NBO.O, and NBO.P). Another former gristmill site was developed for textile manufacturing by Phineas, Joseph and Isaac Davis 2nd, beginning in 1832. The Davis brothers built a brick cotton mill and three brick worker tenements, hauling cotton to the site from Boston by ox teams. From 1859 to 1864 the mill was run by L. S. Pratt of Grafton, and then by Caleb T. Chapin, who gave the name Chapinville to the area. When the cotton mill burned down in 1869, Chapin replaced it with a much larger brick woolen mill. The mill was operated by Ezra Chapin, the son of Caleb T. Chapin, and then by the Northborough Woolen Mills. In addition to the three brick former tenements inventoried in the first phase, surviving resources formerly associated with the Chapinville mill include the 1882 office (7 Chapin Court, NBO.52) and the former company store and post office (317 Hudson Street, NBO.41). In addition to these small textile operations, Northborough residents created many different manufacturing enterprises, at one time or another producing shoes, combs, jewelry, piano keys (the sharps and flats), furniture, carriages, spokes, leather products, baked goods, creamery products, ice, bricks, firearms, dyes and other chemicals, drop forgings, cash registers, movie projectors, and camera equipment. Indeed, the sheer variety of Northborough products is one of the chief defining characteristics of the town’s industrial history. Of these, perhaps the most distinctive was the town’s involvement with comb-making, which began in 1839 with the Bush and Haynes shop on Whitney Street, with power supplied by Howard Brook. Soon other comb-makers set up shop wherever space and power for machinery was available; the business directory accompanying the 1857 map of Northborough listed five separate comb-making enterprises. The combs were chiefly made from horn and hooves that were byproducts of local slaughterhouses, with some manufacturers also turning the material into buttons. The largest-scale comb-making enterprise was the Walter M. Farwell factory on Hudson Street south of River Street (NBO.255), which is said to have employed as many people as ever worked in comb-making in Northborough before. In addition to horn, some of which was imported from South America, the Farwell plant made combs out of celluloid, an early plastic. In the 1920s, the plant was converted to textile production by Whitaker & Bacon of Boston, which operated it as the Arlington Shoddy Mill. The survey documented two former shop buildings, the “Old Barn Shop’ (11 Blake Street, NBO.236), where combs, jewelry, shoes, corsets, and buttons are all known to have been made at one time or another, and the former E. H. Smith bone and gristmill (88 Main Street, NBO.95). Northborough’s small-shop industrial history is also recalled by the ca. 1860 stone dam on the Assabet River just south of Main Street (NBO.906) and by the numerous houses associated with the shops’ owners: for example, 47, 55, and 110 Hudson Street and 130 and 140 Main Street (NBO.110, 254, 259, 276, and 277). The survey included dozens of houses associated with individual sawmill operators, comb-makers, and other factory workers. The River Street Neighborhood (NBO.Q) was developed in the late 19th-century predominantly as rental properties targeting the industrial working class. Commerce Although most residents in the period pursued agriculture as the chief source of their livelihood, Northborough developed a small commercial center at the junction of Main Street, West Main Street, and Church Street. As early as 1830, there were two taverns and three stores along what is now modern-day Route 20, and by 1873 the village center could boast of several general stores, a bank, an insurance agency, a saloon, a meat market, a cigar shop, a shoe store, a hotel, two livery stables, and a tin shop. Later commercial enterprises include a Chinese laundry, millinery shops, a jewelry store, a hardware store, pharmacies, and a bicycle shop. Several historic resources associated with the town center’s commercial life were inventoried in the first phase of the survey. Additional resources from this phase include a former general store and bakery (19 Blake Street, NBO.237), the former Northboro Hardware store (17 South Street, NBO.312), and the homes of numerous livery operators, store owners, and bank employees whose livelihoods were derived from Northborough’s commercial prosperity. Transportation Transportation improvements have played a steady role in sustaining the life of Northborough. Although only present-day Route 9 in the southwest corner of Northborough was part of the early 19th-century turnpike system, the road represented by Route 20 and East Main Street was an important road in the colonial period and it remained a busy road throughout the 19th century and even down to the present; the taverns, shops, and stores shown on Valentine’s 1830 map can be attributed in part to business generated by the road. In the railroad era, Northborough was initially passed by in the construction of the first railroad between Boston, Worcester, and points west, as was Framingham Center. But in 1849 the Boston and Worcester Railroad constructed a spur to Framingham Center, and the Agricultural Branch Railroad extended it further westward, completing it to Northborough in December 1856. When this line was further extended to Pratt’s Junction in 1866, Northborough shippers and travelers had not only a direct route to Boston, but also connections to Fitchburg and Worcester. The line became the Boston, Clinton and Fitchburg Railroad in 1869 and, following additional mergers, was renamed the Boston, Clinton, Fitchburg and New Bedford Railroad in 1876. In 1879, it became part of the Old Colony Railroad’s system, which in turn was absorbed by the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad in 1893. In addition to economically sustaining Northborough farmers and merchants, the railroad altered the geography of the center of the village, where it built a passenger depot, freight station, and engine house. Businesses, especially those dealing in bulk products such as lumber, coal, creamery products, and grain, gravitated toward the freight station area, and businesses that catered to travelers, such as a barber shop, livery stables, restaurants, and a pool hall, were located across Main Street from the passenger depot. Today, the importance of the railroad in Northborough’s history is memorialized by two 19th-century stone-arch bridges (NBO.923 and 924) and a crossing shanty relocated as an outbuilding at 44 School Street (NBO.307). Northborough was also served by an electric railroad. The Worcester and Marlborough Street Railway was chartered in April 1897 and began operating in the middle of August. The line connected with another street railway in Framingham, thereby allowing one to travel between Boston and Worcester entirely on the electric cars; in Northborough, the line followed Main Street, where there was a small passenger station opposite the steam railroad’s depot. The steam-powered electric generating plant (inventoried in the first phase) and a car barn were located on Hudson Street in Northborough, and there was another large car barn and office on South Street. Later known as the Worcester Consolidated Street Railway, the line continued in operation through the 1920s. In addition to carrying passengers, street railways of the period usually offered limited freight and express service, which appears to have benefited many Northborough farmers. Military Service During the period represented by this phase of the survey, Northborough experienced the momentous effects of the Civil War. Out of a population of 1,500, Northborough furnished 143 soldiers for the Union Army. Twice as many Northborough men died in the Civil War as in all subsequent wars combined, and for many of those who survived, their service remained an important part of their identity. Northborough had a G.A.R. hall on Main Street until 1922, when it was destroyed by fire. Phase I of the survey inventoried the Northborough Soldier’s Monument, the town’s chief historic resource associated with the Civil War, but many of the houses in town also have an association with men who served, and their service is noted on the forms. Another aspect of this theme was the home-front effort during World War One. The forms note the many contributions of Northborough residents to Liberty Loan and other war-related activities Ethnic Diversity Like much of New England, Northborough became more ethnically diverse during the period covered in Phase II of the survey. The town remained predominantly “Yankee” and Protestant, but after mid-century the population began to include people of immigrant heritage as well: Irish-Americans who came to work on the railroads, French-Canadians associated with the woolen mills, and people from maritime Canada, such as camera-innovator Thomas H. Blair. Around 1900, additional immigrant families from Eastern Europe, Italy, and Armenia added to Northborough’s cultural mix. While there are no historic resources associated with specific ethnic identities (the present Roman Catholic Church is a modern building), the owners or occupants of many of the houses included in the survey reflect the range of Northborough’s ethnic origins. The houses also document the economic success of some individuals of immigrant heritage, such as the home of Irish immigrant and plumbing-supply merchant Thomas Brennan (50 School Street, NBO.309). Northborough did not have ethnic neighborhoods as clearly defined as those in the cities, but small concentrations of particular ethnic groups could be found, such as Irish homeowners on Pleasant Street, French-Canadians in the houses nearby the mills, and people from maritime Canada on East Main Street. Education Northborough’s remaining one-room district schools and the brick Center School on School Street were inventoried in the first phase. This phase continues the history of the community’s efforts to provide its children with appropriate settings for education with its inclusion of the Northborough High School (63 Main Street, NBO.97), built in 1939 as a completely modern facility with large, bright classrooms, laboratories, a library, and an auditorium/gymnasium. Community Planning and Development In the early 20th century, Northborough developed some of the institutions characteristic of larger towns and cities in order to meet the needs of its growing population. In addition to the public library inventoried in the first phase, this theme is embodied in the building at 11-13 Church Street (NBO.64), built in 1926 to house the town’s fire department and police services. Architecture In addition to their historical associations, many if not most of the resources included in this phase of the survey also are notable as examples of particular styles of architecture popular in the period. Because Northborough was predominantly a rural community, dwellings are mostly modest, vernacular interpretations of popular styles, rather than extravagantly detailed high-style examples. Greek Revival-style houses have pilastered corners and pilaster-and-lintel entries, rather than full porticos, and Victorian houses tend to be eclectic, with brackets, window trim, porch-post turnings, and gable-peak ornaments freely drawn from a variety of more formal styles. Still, Boston and Worcester were not far away, so there are a few surprises, such as the extraordinary portico of the Greek Revival Wilder Bush House (27-29 Whitney Street, NBO.80); some well-preserved, densely-bracketed Italianate houses (31 Pleasant Street, NBO.286, and 220 Whitney Street, NBO.327); and small 1 .-story houses that incorporate the distinctive Mansard roof of the Second Empire style (234 Whitney Street, NBO.328). Three of the Victorian houses inventoried in this phase have exceptional Queen Anne-style detailing; all were associated with the former Daniel Wesson estate known as “The Cliffs” (NBO.278, 279, and 280). Twentieth-century architecture is represented in Northborough by the Art-Deco detailing on the former Northborough High School (63 Main Street, NBO.97) and by the Vera Green House (333 Howard Street, NBO.251), an outstanding example of the influence of Frank Lloyd Wright’s “organic architecture” in the post-World War II era. Two notable aspects of Northborough history are associated with activities whose main focus was outside the town’s borders: the creation of reservoirs and aqueducts for the Boston metropolitan water system, and the establishment of the Westborough State Hospital, the grounds of which extended into Northborough. Because both are represented by existing National Register of Historic Places listings (Wachusett Aqueduct Linear District, Water Supply System of Metropolitan Boston Multiple Property Submission, 1990; Westborough State Hospital, Massachusetts State Hospitals and State Schools Multiple Property Submission, 1994), no additional resources associated with these two historical developments were included in this phase of the survey. Although the main purpose of the survey was to identify the properties’ associations with important Northborough historical themes, the forms also endeavor to include “local color” whenever known. Examples include the barn located near the field where the “Northborough Mastodon” was discovered in 1884 (536 West Main Street, NBO.326), the gym where numerous notable early 20th-century boxers trained (11 Blake Street, NBO 236), and the home of blacksmith/homing pigeon-breeder George Burgoyne (157 South Street, NBO.317). SOURCE: Public Archaeology Survey Team, Inc. Phase II Historic Properties Survey, Town of Northborough, Massachusetts: Final Survey Report. http://www.town.northborough.ma.us/Pages/NorthboroughMA_BComm/Historic/nhc/Final_Reports/Final_Report_Phase_II.pdf : 2014. |

AuthorBeth Finch McCarthy

|