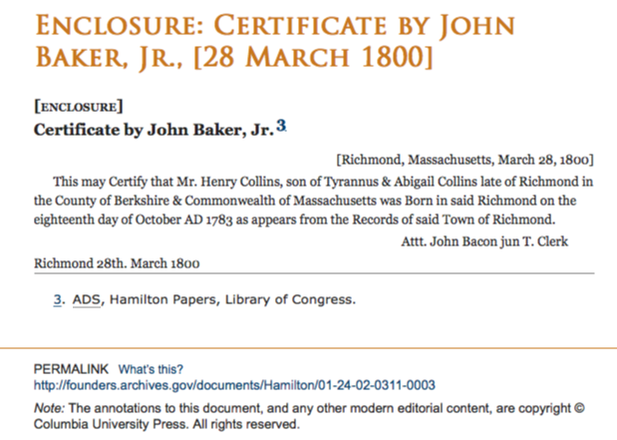

The RecordsThe National Archives has partnered with the University of Virginia to make historical documents of the Founders of the United States of America free and available online. On the website Founders Online, you can search through thousands of digitized records from George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. The site is continually being added to and will include over 178,000 documents relating to America's Founding Era when it is completed. To get started, there is a FAQ page "How to Use This Site" for tips on how to find, access, and research documents in the collection. Whether researching a person, time period, or a concept (e.g. Bill of Rights), you can find specific suggestions and helpful information there. The collection can be searched in several ways: by author, recipient, time period, or keyword. The documents are fully searchable and annotated. The Case StudyAs an example of how valuable this digital collection can be for genealogists, I will use a case where I was working on identifying the death date of a Revolutionary War patriot from New York. If you have ever worked with colonial era records, then you know it is often difficult (if not frustratingly impossible) to locate documents for an ancestor going back that far. Some states, and even towns within a state, were better than others at keeping track of vital records at that time. After exhausting town and church records search, the goal is to look next for other types of records that hold clues about that ancestor. In the case of my patriot, I needed to track his family's whereabouts after the Revolutionary War ended. What little I knew about him was that he was born and had married in Connecticut, and moved to the small frontier town of Ballston, New York when it was first settled. During the Revolution, he was taken prisoner by raiding Tory soldiers and held in Canada until the fall of 1782, when the last of the Patriot prisoners were released and sailed for home. Unfortunately for me, he did not go straight back to his farm in Ballston, NY. After the raid where he was taken prisoner, it was apparent that his wife and children had not remained in the town. They had probably fled to be near extended family or former neighbors in a safer place, but where?? At that early stage in my research, locating that unknown community was like finding a needle in a haystack. The ancestor's first name was unique ("Tyrannus") but also frequently misspelled in records, so using name variations and wildcard characters in searches could take a very long time. Last name was common ("Collins"), which would also return too many records during index searches to be productive either. When it comes to colonial research, as I have already mentioned, vital records can only be so helpful. Census records are the next go-to place, but the first U.S. census of householders are fraught with errors and omissions. Because the family didn't show up in the first 1790 U.S. federal census in either New York or Connecticut, I needed to strategize another way to get a handle on where they might have gone. The first stop was to look at early post-colonial era collections for general information that might pertain to the ancestor and his family. That is where the Founders Online collection came in. It truly was as simple as typing the ancestor's name "Tyrannus Collins" in the keyword search bar. Of course, we all know about serendipity, which isn't always on a researcher's side. But when it is..."Eureka!" moments like this are priceless: I not only found the town where the patriot had gone right after the war, I also confirmed that his youngest child was born there and that they had left town afterwards. I have since identified much more about the patriot's personal story up until his death and I owe it to this simple affidavit for helping knock down a brick wall that has made other researchers give up. Source: Founders Online. https://founders.archives.gov. 2017

1 Comment

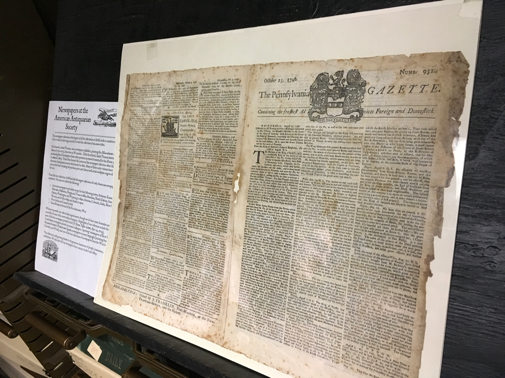

Today I visited the American Antiquarian Society (AAS) in Worcester, Massachusetts where Jim Moran, the AAS’s Director of Outreach, arranged with the local group History Camp-Boston for a special behind-the-scenes talk and tour. This incredible archive is the repository for all things printed in our country’s 50 states, ranging from 1640—1876. These dates directly correspond with the operation of the first printing press in Boston through the enactment of copyright laws by the Library of Congress. In 1876, 2 copies of any publication made in America were required to be sent to Washington; because the LOC had a stable and larger infrastructure for housing the materials, the AAS cut off the collection as of that year and turned its focus to acquisition. This strategy has made the AAS an archive of national scope that every researcher should include in his/her go-to repository list. About the AASThe AAS was founded in 1812 by Revolutionary War patriot and local printer Isaiah Thomas. During the colonial years, when he ran his own very successful business in Massachusetts, his passion was to collect samples of publications from printers throughout the colonies. He wanted to study and compare technology and materials, with the collateral result of amassing an important historical collection. This was the birth of the AAS as both a learned society and a major independent research library. The Collection The AAS library today houses the largest and most accessible collection of books, pamphlets, broadsides, newspapers, periodicals, music, and graphic arts material printed through 1876 in what is now the United States. Predating the New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS) and New York Genealogical and Biographical Society (NYG&BS), the AAS also holds manuscripts and a substantial collection of secondary texts, bibliographies, and digital resources and reference works related to all aspects of American history and culture before the twentieth century. Types of ephemera run the gamut from 1814 voter ballots from a single town to inserts that were tucked into boxes with new watches. Most impressive, however, is the scope and depth of the newspaper archive. Access the ManuscriptsThe collection has been fully digitized up through 1820, with finding aids for the subsequent years. The entire digital collection can be accessed on site at the AAS. Remote (at-home) access is available for a small portion of the collection. Where AAS has partnered with outside vendors, such as GenealogyBank.com and Ancestry.com, the vendors only have a portion of the full collection in their databases. If you are planning to research on site at the library, visit the AAS website for how to plan and what to expect. The library is closed-stack and non-circulating. Visitors fill out call slips for item retrieval and view the materials in the reading room. Non-flash photography is encouraged, with photocopying and digital imaging services also available. Typesetter Trivia!The metal letters used in hand setting a printing press were stored in a case of wooden drawers next to the printing press. This is Isaiah Thomas's actual LETTER CASE on display at the AAS, To be time efficient, and to be able to work quickly without looking, typesetters arranged the letter blocks in a specific order: the most frequently used letters were placed in the LETTER CASE where they could be reached easily. Specifically, the capital letters were stored in the UPPER CASE and the regular letters were stored in the LOWER CASE. (And now you know where those terms originated!) American Antiquarian Society

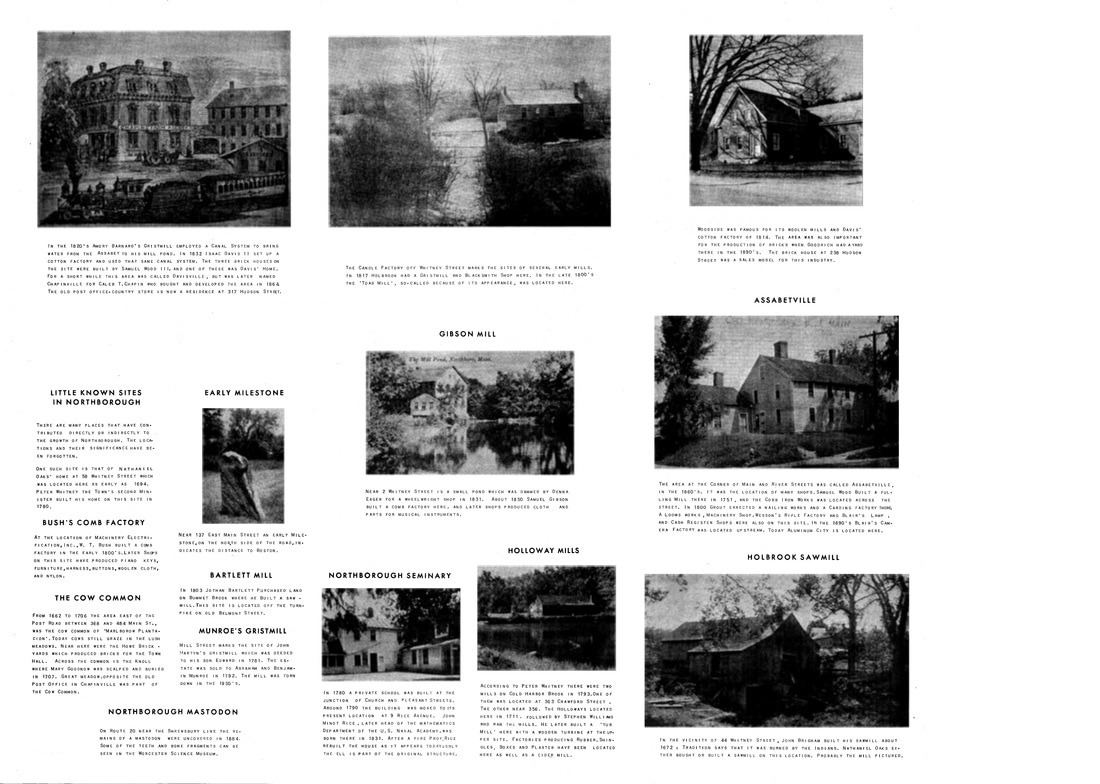

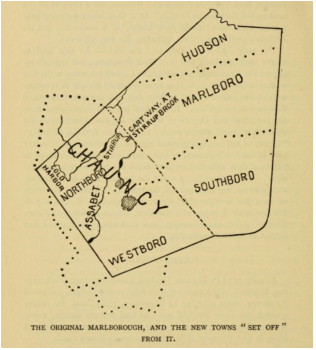

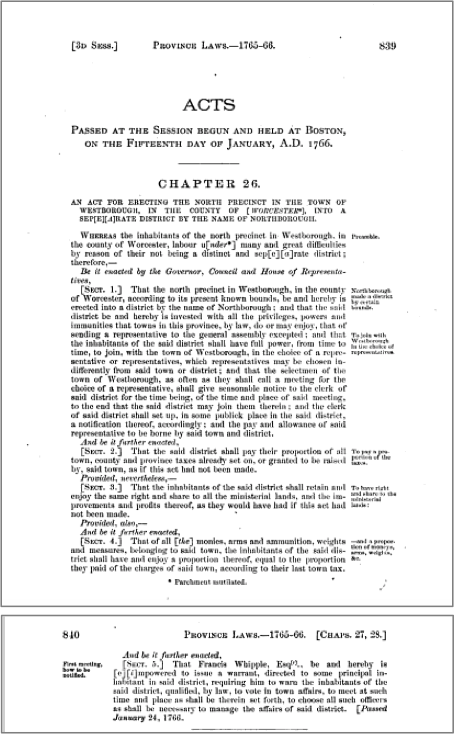

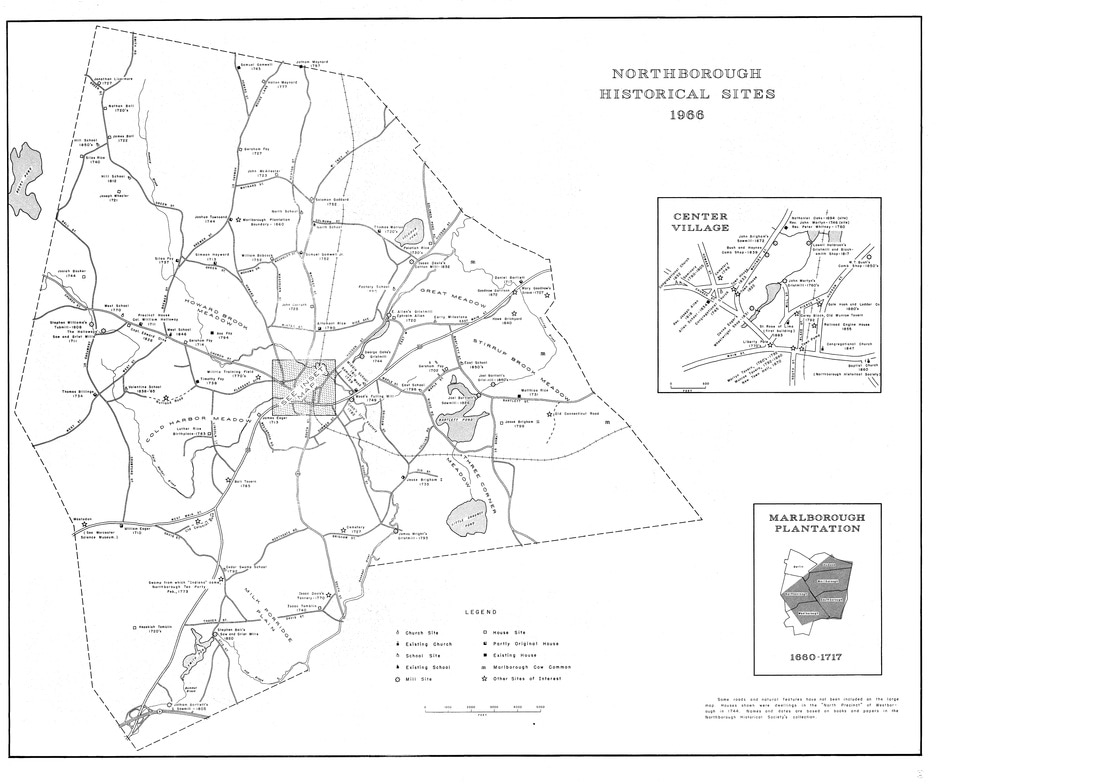

Address: 185 Salisbury Street, Worcester, Massachusetts 01609 Tel.: 508-755-5221 Email: [email protected] Website: www.americanantiquarian.org In 1966, the town of Northborough, Mass. celebrated its 200th anniversary of becoming a town. The first inhabitants on the physical land were there decades before the 1766 separation from the parent town of Westborough. This map, created by the Anniversary Committee in 1966, identifies many of the historical homesites going back to 1660. While the general layout of the town hasn't changed much over the last 50 years, one major event changed the character: the building of Rt. 290. In the sections where the highway overpasses could not be built, roads were either rerouted or cut in 1/2 and turned into cul-de-sacs. So if you are headed for an address on Howard Street, you'd best check a map first to see which end you have to get to first! A full size version of the map is here.  1966 Map of Northborough (Worcester Co.), MA with Historical Sites Overlay. Front view. (courtesy Northborough Historical Society) 1966 Map of Northborough (Worcester Co.), MA with Historical Sites Overlay. Front view. (courtesy Northborough Historical Society) Map of original Marlborough Plantation with modern town overlay (from The History of Westborough) The way New England towns were settled by the English was actually very common across Massachusetts. Religious dissenters (primarily Puritan) established communities where there was plenty of land and other natural resources and followed traditional English laws. Towns were built around the Meeting House, the central location of all things religious and political. Residents were primarily farming families. Couples bore many children to work the family farms and faced the odds of losing some to diseases like smallpox or the flu. After a few generations in those early communities, there was not enough open land for the increasing number of growing families. Surveyors headed westward to find new areas for establishing new towns. For example, the early colonial town (or “Plantation”) of Sudbury, Massachusetts became crowded and a handful of young men set off to find a new home in the adjacent combined lands of what is now Marlborough, Hudson, Northborough, Westborough, and Southborough. In that manner, "Marlborough Plantation” was settled in 1656 and the first settlers lived near the center of modern Marlborough, farming land in the outer areas of the town. Over subsequent generations, families continued to grow in number and needed to find more living space outside of the center of Marlborough Plantation. A village a few miles west at Lake Chauncy sprung up (the "west borough"), where farmers of the western stretch of the Plantation (Northborough and Westborough combined) could live closer to where they worked during the day. However, the new village was inconveniently far from the Plantation Meeting House; it was a slow and hilly trip back to the meeting house every Sunday. It followed that once there was enough people living in Chauncy to warrant building their own meeting house, hiring their own minister, and “managing their own affairs,” the villagers petitioned for separation from Marlborough. In 1717, the new independent town of Westborough was officially established and comprised the lands of modern Northborough and Westborough. When the Westborough meeting house moved from Lake Chauncy to three miles south to the center of modern day Westborough, there were well over 30 families living in the “north part” of the town who again found themselves facing a very long and difficult trip back and forth on required meeting days. Can you just imagine the families, on an early wintery Sunday morning, trying to be up, dressed, and ready to march down the hazardous road [what is now Rt. 135] to church in Westborough Center? The devoted northern Puritan families were outraged even more by the inequity of their situation when finding themselves at funerals without a minister; he himself did not like to make the long trek up north to Brigham Street Old Burial Ground. To address these religious concerns, the northern family heads met and petitioned in 1744 to become a precinct of Westborough. Note that a “precinct” was distinctly different from a “town”: the newly formed Northern Precinct would have its own meeting house and preacher but would remain politically and fiscally a part of the town of Westborough. Over the two decades following the 1744 petition, there were lingering serious challenges because the Northern Precinct was not fully independent from Westborough. For example, elected northern officials found it difficult to travel south to important town meetings and represent the interests of the northern families. Another problem was that the Northern Precinct was viewed as only one of the town's three school districts and the teacher was not available full-time in any single district. Adding fuel to the flame, no funding was made for Northern Precinct schools, highways, or other types of community improvements. To finally achieve the independence they had sought and desired for so long, town founders successfully presented a petition to the General Court in Boston. The District of Northborough was officially formed on the 15 January 1766 and the district became a fully-fledged town on 23 August 1775. SOURCES: Clifford, John Henry et al. The Acts and Resolves, Public and Private, of the Province of the Massachusetts Bay: to Which are Prefixed the Charters of the Province with Historical and Explanatory Notes, and an Appendix, Volume IV. Boston, Massachusetts: Wright & Potter, 1890. DeForest, Heman Packard and Edward Craig Bates. The History of Westborough, Massachusetts. Westborough Massachusetts: Town of Westborough, 1891. Kent, Josiah Coleman. Northborough History. Newton, Massachusetts: Garden City Press, 1921. Parkman, Ebenezer. The Diary of Ebenezer Parkman (1703-1782): First Part, Three Volumes in One (1719-1755). Francis G. Walett, editor. Worcester: American Antiquarian Society, 1974. Happy 250th Birthday, Northborough! |

AuthorBeth Finch McCarthy

|